REDUX

When four underfunded young geniuses are forced to work together, their synergies unleash transformative technologies.

It worked.

I’m back, and I’m dying—probably radiation exposure from forcing temporal flow in reverse. The nausea hits in waves. Don’t have much time.

As I throw up in the bushes behind Anderson Hall, I want to blame someone else. Darryl’s recklessness. Pam’s curiosity. Charlotte’s brilliance. But it was my hubris that brought this to pass. Mine alone. I’m the one who thought we could improve on four billion years of evolutionary refinement with six months of graduate-level arrogance.

The campus looks exactly as it did that night in 2075—the night we thought we were saving the world. The maples are still young, the biotech building still has that new-construction smell of printed concrete and optimism. We were going to rid humanity of sickness, disease, disfigurement. Our genomic recombinator would erase junk DNA, optimize expression patterns, give everyone access to the biological lottery winners’ genes.

I thought no government could be trusted with this technology. Every simulation we ran showed the same outcome: weaponization within eighteen months, genetic castes within a generation. So I made the decision that damned us all—I would release it open-source. The hardware wasn’t complex; we’d built it from lab equipment and 3D-printed components. The real breakthrough was the software, the algorithms for safe resequencing that took us three years to develop.

The algorithms weren’t safe.

After the mice and cats, we needed human trials. We knew no institutional review board would approve it, not for decades. We became our own test subjects. How arrogant is youth? How could we know?

If we had been more patient, if we had run the simulations for another year, we would have learned about the toxic genomic introductions—the genes that evolution had carefully separated, buffered, ensuring their benefits released slowly into the population across generations. Nature was smarter than we were. She knew some genes shouldn’t express together, not in the same organism, not without the regulatory framework that took millennia to evolve.

We thought we could do better.

We bred stronger, faster, smarter mice. Their muscle density increased forty percent. Their problem-solving abilities approached corvid-level intelligence. We expanded the cognitive capacity of cats, altering their neurology, increasing their cerebral cortex size by thirty percent. We made the world’s most efficient predator smarter, more adaptable, more lethal.

It seems stupid in hindsight. It was stupid in the moment. We just couldn’t see it.

Darryl was the first to die.

He was the first of us to truly embrace what we’d created, the first to see it not as a research tool but as salvation. Lou Gehrig’s disease was eating him alive—had been since he was nineteen. By the time we completed the recombinator, he could barely move his fingers. His mind was sharp as ever, trapped in failing flesh.

He configured the device alone, at night, inputting his own parameters. He didn’t tell us. He knew we would have said no, insisted on more testing, more caution. He couldn’t wait. Wouldn’t wait.

We found him the next morning lying beside his wheelchair, one hand still reaching toward it. His body was perfect—muscular, symmetrical, beautiful in the way classical sculptures are beautiful. His eyes were open, still brilliant blue, still intelligent.

Still.

We were not deterred. We had to know what happened. We studied him for weeks, down to the cellular level, the genetic markers, the expression patterns. His work was technically flawless and fatally flawed. He had removed the SOD1 mutation, yes. But in optimizing the surrounding regulatory genes, he’d removed the buffers that limited the disease’s progression. The recombinator had worked perfectly—rewriting his genome even as the unbuffered disease ravaged his motor neurons at ten times the normal rate.

It was a matter of timing. His cure killed him faster than the disease would have.

We should have stopped then. Any rational scientists would have stopped.

We were more determined than ever.

Pam went next, but she was careful. Methodical. She made only physical changes, one modification at a time, waiting weeks between sessions to document the effects. Increased bone density. Enhanced muscle fiber recruitment. Optimized metabolism.

On day forty-seven, she decided to begin neural modifications. Minor ones—just increased synaptic density in the hippocampus, better memory formation. We watched through the observation window as the recombinator’s field enveloped her, the shimmer of quantum-state manipulation visible as a faint aurora around her body.

The process completed normally. All indicators green. Charlotte was already moving toward the tank release when I glanced back at the observation window.

The tank was empty.

Not empty like she’d gotten out. Empty like she’d never been there. No residual recombinant fluid. No biological matter. No Pam. The sensors showed the process had completed. The logs showed successful genomic integration. The tank showed nothing.

We searched for three days. Ran every scan we had. The matter that had been Pam—sixty-three kilograms of atoms—was simply gone. Not destroyed. Not transformed. Gone. The energy balance was wrong. Conservation of mass violated. It was impossible.

We didn’t know what happened to Pam, but working alone had clearly become a liability we could ill afford. The local police had begun investigating our lab—two missing persons, both last seen with us. We became people of interest. In their search of the facility, they accidentally released our modified animals. Six cats, fourteen mice, scattered into the ecosystem.

It seemed like such a small thing at the time.

We realized this was a problem of consciousness, of mental capacity. Some threshold we didn’t understand, some barrier between physical and mental modification that we’d crossed without recognizing it. Charlotte decided she would go next, but differently. She would document everything, modify her brain first, understand the process from the inside.

Strong-willed, physically fit, brilliant—she thought she could maintain herself through the transformation. She started with neurotransmitter optimization, then synaptic density, then neural pathway efficiency. Each change carefully logged, measured, documented.

For the first week, it was miraculous. She created patents for technologies we couldn’t even fully comprehend—quantum processors using biological substrates, gravity manipulation through folded spacetime geometries, things that shouldn’t be possible with our current physics. Her handwriting remained steady, her personality intact.

On day eight, she stopped talking.

She typed instead, her fingers blurring across the keyboard. Three hundred words per minute. Four hundred. Five hundred. Her eyes never left the screen. She ate only when we forced food into her hands, drank only when we held water to her lips.

She wrote for five more days.

On day twelve, blood began seeping from her ears. She didn’t stop typing. On day thirteen, the vessels in her eyes burst, blood filming across the whites, the blues. She still typed, her fingers finding keys with perfect accuracy despite total blindness.

She wrote dispassionately, clinically, until the very end. Nothing mattered but transferring the information from her expanding consciousness to the page. In those last minutes, when she could neither see nor hear, I finally understood what had happened. What was happening to all of us.

Her final entry: “Neural density increasing beyond physical substrate capacity. Consciousness desynchronizing from baseline temporal flow. Experiencing probability manifolds as discrete sensory input. Cannot recommend this path. Cannot stop the process. T—if you’re reading this—STOP THIS. Burn it all. The cats will—”

She died at the keyboard, her fingers still moving, typing nothing.

I archived everything. Set it to mail to my father—he would know what to do with her notes, her warnings, her terrible final discoveries.

Then I entered the recombinator myself.

I had to know. Had to see it for myself.

After thirteen days of transformation, following Charlotte’s exact protocol, I walked out of the lab. The moment my foot touched the grass outside, I stepped through Time.

For the first year—subjectively—nothing moved. The world froze around me. I felt neither hunger nor thirst. For me, only seconds appeared to pass. I was a blur in photographs, a whisper of wind, an echo in a silent room. To the world, I must have been invisible, moving too fast to perceive.

Then something went wrong.

I stopped moving. The world didn’t.

Days blurred together, the sun becoming a continuous arc of light overhead, painting its path across the sky in a single luminous band. Seasons flickered past—green to gold to white to green. I stood in the middle of what had been our campus as it transformed around me. Buildings rose and fell. The city grew, consumed the landscape, then began to crumble.

Charlotte’s notes had predicted this. We weren’t moving through time linearly—we were desynchronized from it, experiencing probability manifolds, seeing possible futures branch and collapse around our decisions. I still didn’t fully understand. I hadn’t dared expand my consciousness as much as she had.

I wasn’t that brave.

Then I saw the flashes of light around me. Familiar. A pattern I should recognize. Charlotte’s words echoing in my enhanced memory: Breathe. Concentrate. Focus. Stop Time.

Years had passed since I’d last thought consciously about breathing. I did it now.

Time slowed. Stuttered. Stopped.

A city had grown around me. Silent. Ruined. Buildings stood like broken teeth, blast patterns radiating from some central catastrophe. Scrawny vegetation pushed through cracked pavement. The sky was the wrong color—too much UV getting through, atmospheric damage on a scale that spoke of cascading ecosystem collapse.

I dropped into the tall grass, instinct screaming danger before I consciously recognized the threat.

Cats. Big cats, easily the size of lions, moving through the ruins with terrible purpose. Their eyes glittered with intelligence, reflecting light like mirrors. A pride of twelve, hunting in coordinated silence.

They’d found prey—a group of bipeds feeding at the edge of the grassland. The bipeds saw them too late. The pride moved with cheetah speed, crossing fifty meters in seconds. The killing was efficient, brutal, practiced.

When the feeding frenzy ended—when the pride finally left their kill—I crept forward to examine the remains.

The bipeds were vaguely human. Huge skulls, twice the size of baseline homo sapiens. Powerful skeletons showing evidence of extreme physical optimization. I looked closer at the bones and saw unique carbon lattice structures, enhancing strength beyond anything natural.

This was our work. Degraded by time. Mutated across generations. Spread through the population.

Charlotte’s last words burned in my mind: “Stop this.”

She’d known. In those final moments of expanded consciousness, she’d seen this future. These futures.

That’s when I heard the howl.

The pride had caught my scent. I watched them turn, their enhanced eyes finding me instantly. They accelerated, kicking up dust, moving with impossible speed and clear, terrible intelligence.

I thought of Charlotte, typing blind and bleeding.

I thought of Pam, scattered across probability space.

I thought of Darryl in his wheelchair, reaching for a life he’d never live.

The cats closed the distance. God, they were magnificent. And they were going to tear me apart.

I changed the flow of Time. Reversed it.

It’s like drinking from a fire hose, every moment of the intervening years slamming back through my consciousness. Cities unbuilding themselves. The planet healing and unhealable. My friends alive and dead and dying in every possible configuration.

There.

There we are, celebrating. Drinking cheap champagne in the lab, toasting our success. So young. So arrogant. So certain we’re going to save the world.

I don’t have long. Vision blurring. The radiation or the temporal stress or both. My enhanced neurons are burning out, I can feel them dying like stars going dark.

I shuffle into our lab. Everything so shiny, so new, so full of promise. The mice in their cages, clever and doomed. The cats watching me with eyes that are already too intelligent, too aware.

I do what has to be done.

I kill the cats first. Quick. Painless as I can make it. They don’t understand, their enhanced minds reaching for comprehension they’ll never achieve. The mice next, their tiny bodies so perfect, so poisonous to the future.

I burn the servers. The backups. Every piece of code, every algorithm, every careful notation that could rebuild our terrible work.

Then I pour the accelerant around the lab, my hands shaking, my vision tunneling.

Most importantly, I ensure that my friends and I become missing persons.

Not dead. Not transformed. Just... gone. Disappeared before we could doom the world. The police will investigate. They’ll find nothing. No bodies. No lab. No evidence of our breakthrough.

Just four graduate students who vanished, and a mysterious fire that consumed an empty building.

As the flames catch, I think about Charlotte’s last words. About Pam scattered across probability. About Darryl reaching for his wheelchair.

I think about the cats with their glittering eyes.

The fire is beautiful. The world blurs. Time hiccups around me one final time.

I hope it worked.

Redux © Thaddeus Howze 2012, revised 2024. All Rights Reserved.

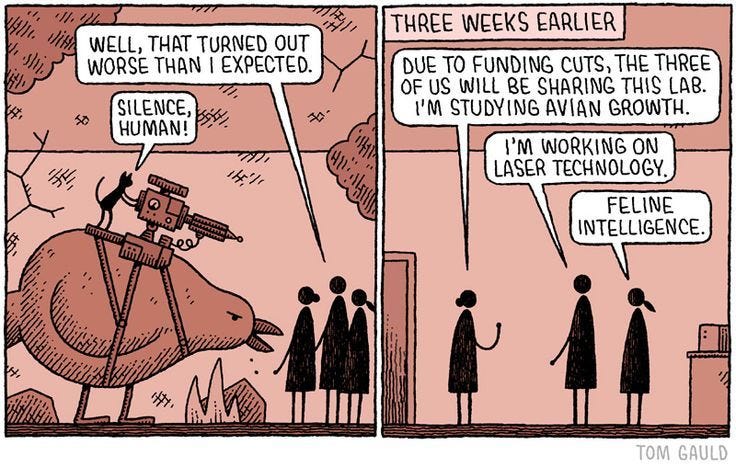

Inspired by Tom Gauld’s cartoon about scientists forced to share a laboratory due to funding cuts, where competing projects in avian growth, laser technology, and feline intelligence inevitably interfere with catastrophic results. What began as Gauld’s characteristic deadpan commentary on institutional dysfunction became this meditation on the tragedy of brilliance without proper infrastructure—and what happens when we enhance apex predators without considering the consequences.

Hurbris...